By Niels Dokkuma, Manager Sustainable Management & Agronomist, Royal Netherlands Golf Federation (NGF)

In the interests of sustainability, human health and the environment, a little bit of disease and a few weeds in the turf are becoming more acceptable.

The pressure to phase out the use of pesticides in public spaces (including golf courses and sport pitches) is radically increasing in the Netherlands. This all started with a European Union Directive in 2000 aimed at improving water quality. As part of this, every member country is now working in its own way to minimise the use of pesticides.

Because the Netherlands is so densely populated with intense use of the limited land available, the Dutch government may potentially go a step further with a total ban on chemical pesticides in public spaces over the next few years. This is due to the public health risk, besides the more obvious, environmental reasons. There are already bans on the use of pesticides on hard surfaces (as of March 2016) and on other areas outside of agriculture/horticulture (November 2017). For sports fields (as well as some other sectors), it was decided that it is not (yet) possible to be pesticide-free and maintain minimal playing quality.

Focus on golf

In light of this, the importance of a planned and credible approach (as a prerequisite for self-regulation) is also growing in the golf sector. In the Netherlands, there have been negotiations between the sport sector and the government, which resulted in a so-called Green Deal. It pertains to the established Green Deal Sport Fields agreement between the Ministry of Infrastructure & Environment, Ministry of Welfare & Sports, the sports sector and suppliers on phasing out pesticide use. Under the agreement, the sports sector takes responsibility for reducing its pesticide use. If enough improvements are made, there may be very few but very limited exceptions possible under a ban.

What does this mean for golf clubs? The essence of the Green Deal Sport Fields agreement comes down to:

• The strong reduction of pesticide use − as much as technically feasible while maintaining minimal levels of playing quality.

• A contribution to the annual monitoring of which pesticides are used, where and for what purpose.

• The implementation of established best practices.

Self-regulation

To address this challenge, a system of self-regulation based on GEO-certification (the Golf Environment Organisation) has been developed by the Dutch Golf Alliance (i.e. the Royal Netherlands Golf Federation, the Netherlands Greenkeepers Association and the Netherlands Golf Course Owners Association). Because GEO enables the golf sector to continue to shape its own future, it will lead to both practicable solutions for golf and acceptable outcomes for society. The catchcry is: ‘Lead the change or change will lead you”.

The target is 125 out of a total of 250 golf courses actively participating towards GEO-certification. Currently, some 100+ courses are GEO-certified and about 20 are ‘oncourse’ to be.

Community involvement

A second building block is working closely with nature-oriented organisations and drinking water companies, to let them have a look at the world of golf course maintenance and to share their views in a systematic way. Then, to let them tell the story of how well golf course maintenance is being done in the light of environmental best practices!

Greenkeeping craftmanship

Independent consultancies for golf course management are heavily oriented towards long-term solutions for playing quality challenges. They are opposed to the short-term, quick fixes promoted by some commercial companies with ‘magic in the box’ products.

The Golf Alliance is heavily focussed on sustainable quality and is making an intense effort to communicate this to golfers at a local level through the clubs and golf courses themselves. It is also encouraging boards and their directors to take responsibility for facilitating stewardship of their land. Last but not least, new efforts are being made to increase the quality of education as the prerequisite for independent knowledge acquisition.

We have to work with nature, not against it with all kinds of quick-fixes, fake solutions and symptom treatments. That sounds easy, but it's often difficult to put into practice. That's why the Netherlands Golf Federation advises golf clubs/courses to start with:

1. Realistic (sustainable) expectations of quality (boards and directors to note).

2. Long-term planning (club managers and greens committees to note).

3. Actual measurements recorded so that maintenance will be based on objective data and not opinions (head greenkeepers/course managers to note).

Course Manager Vincent de Vries of GC De Hoge Kleij (left) monitoring the turf it’s sward composition for common bents, fine fescues, limited thatch and long roots with NGF’s Niels Dokkuma (right).

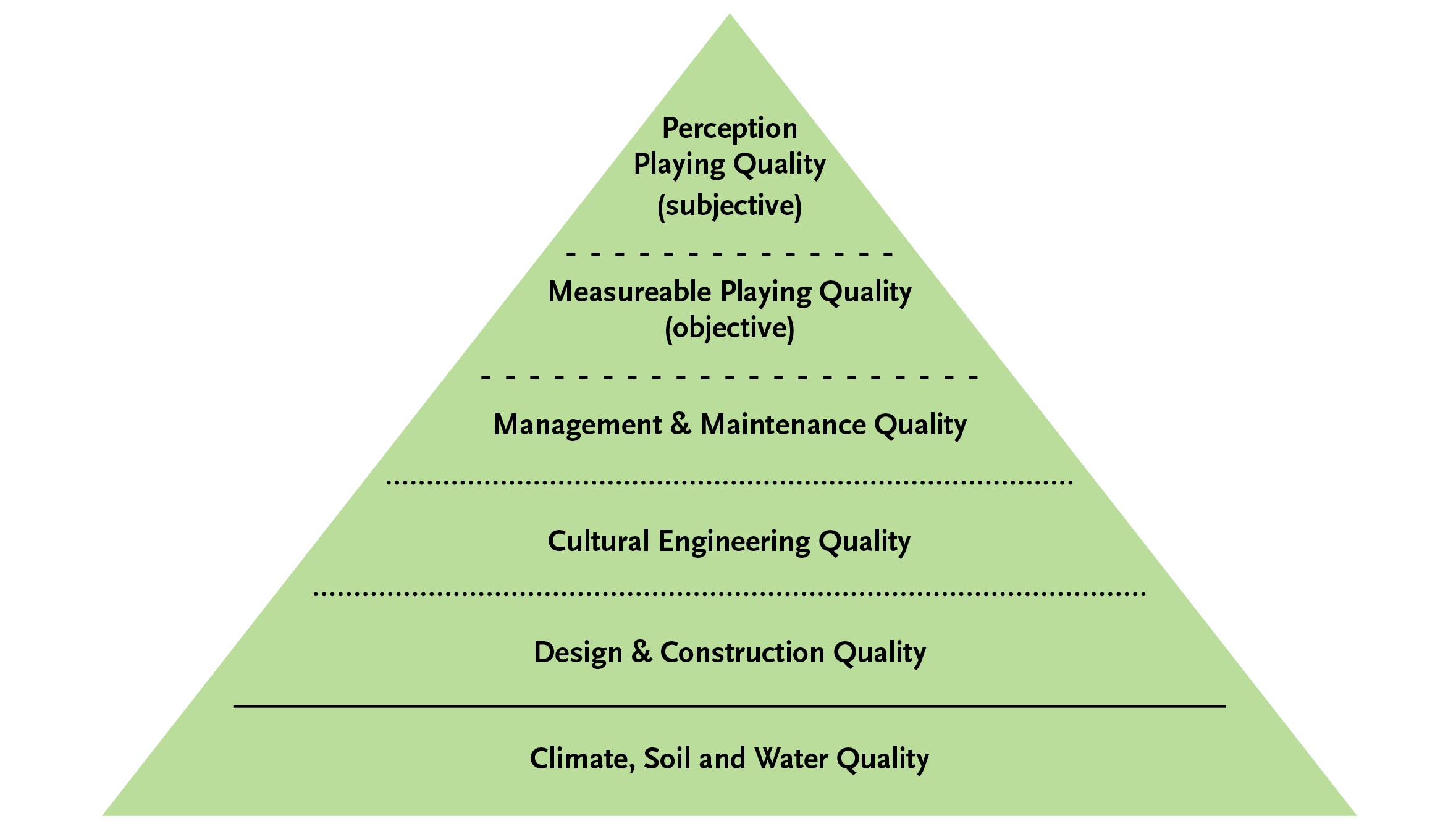

However, a broad foundation must be in place in order to achieve longer lasting playing quality (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Agronomy Pyramid demonstrates the importance of a strong foundation and the inputs necessary to achieve long lasting playing quality. © NGF

In order to maintain the quality of play (i.e. the highest content of fine fescue and common bent) on a sustainable (long-term) basis, focus must be on the basic care of greens1. This needs to be supported by regular and objective measurements of the course characteristics.

This involves us all

It’s our responsibility to prepare golfers for change and to accept that a green will sometimes contain just a little bit of disease and a fairway some weeds. The question is: does this really affect playing quality or do we just not like how it looks?

Reference

1. ‘Practical Greenkeeping’ by Jim Arthur (1997, revised 2003)